Hungary is expanding logistics hubs near the Ukrainian border.

The Hungarian government is openly prioritizing the attraction of large foreign investments from both the West and the East, with a particular emphasis on Chinese investments. These include factories for battery and electric vehicle production, as well as major infrastructure projects like the reconstruction of the Budapest-Belgrade railway. One element of this strategy is the creation of a network of logistics parks. Logistics currently account for 5% of Hungary’s GDP, and the government aims to increase this share to 10%. To implement these logistics projects, Hungary’s Ministry of Economy forecasts their placement on 340 hectares at an estimated cost of around 370 billion forints (€951 million).

On February 21, the Hungarian Ministry of Economy announced the creation of 18 new logistics parks and the expansion of several existing ones. This essentially means not the creation of new enterprises but an open competition to integrate existing parks into the national network to unify operational requirements and enhance competitiveness through various preferences. Logistics parks that operate on at least 3 hectares and have 3,000 square meters of warehouse space can participate in the competition. Depending on their scale, these logistics parks can qualify as intermodal, regional, or local. For Hungary, the development of logistics as a crucial component of its economy is logical, given that the country is crossed by three major (Pan-European) road freight routes: East/Eastern Mediterranean from the Slovak to Romanian borders through Budapest, the Mediterranean corridor from the Croatian border to the northeast to the Ukrainian border through Budapest, and the Rhine-Danube corridor from the Slovak border to Budapest. Additionally, there are two branches: one to Romania (parallel to the East-Eastern Mediterranean corridor) and the other to Croatia and Serbia. Moreover, a network of expressways is available throughout almost the entire country.

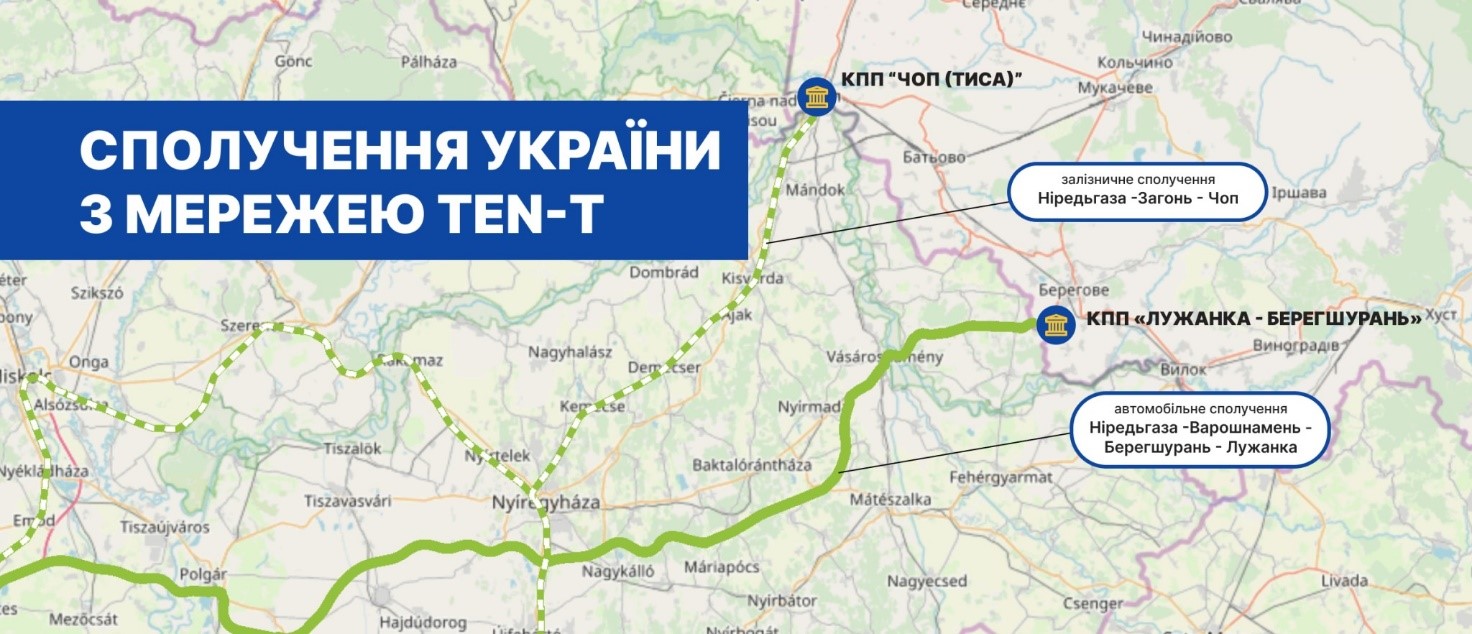

Ukraine has taken a course towards building “pragmatic” relations with Hungary, so it is essential to approach the use of all potential opportunities without emotions. Since Chinese and other investments are coming not only to eastern Hungary but also along the entire southwestern border of Ukraine, forming a kind of “automobile belt,” it is worth integrating into it, making the border zone infrastructure on the Ukrainian side a gateway to Europe. At least two of the planned 18 logistics hubs will be located close to the Ukrainian border: in the town of Fényeslitke, where construction of Europe’s largest intermodal rail terminal, East-West Gate, began in 2021 (less than 30 km from the border), and in the town of Záhony (8 km from the border). The key to using the proximity to these border logistics facilities in Ukraine should be connecting to the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T).

This direction should be considered from two perspectives: logistics and military mobility.

Logistics: The investment belt along Ukraine’s western border coincides with the TEN-T map, with Ukraine interested in joining the Mediterranean corridor of this network, which connects the ports of Algeciras, Cartagena, Valencia, Tarragona, and Barcelona on the Iberian Peninsula with Hungary and practically reaches the Ukrainian border, and southern France, northern Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia.

In 2024-2026, the Ukrainian government intends to continue modernizing existing and opening new checkpoints with EU countries, addressing the challenges involved. The primary goal is to implement joint customs and border control with neighboring countries at these checkpoints. Currently, there are 21 road checkpoints on the border with EU countries. About 10% of Ukraine’s cargo flow passes through Hungary, considering the insufficient capacity of the Ukrainian-Hungarian border.

Military Mobility: The EU’s Action Plan on Military Mobility, initiated in 2018, with a new version covering 2022-2026, aims to ensure the swift and seamless movement of military personnel, materials, and assets within and beyond the EU. This must be possible in short terms and on a large scale. Given Ukraine’s Euro-integration processes and intentions to join NATO, this is also a crucial aspect of infrastructure development and integration into the TEN-T network. Currently, military mobility involves 25 EU member states (including Ukraine’s neighbors) and the United States, Canada, and Norway as partner countries. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has prompted Europe to ensure the rapid movement of military assets within the EU for quick responses to threats or emergencies, as well as the swift transfer of military aid.

The relevant standards—EU military requirements—governing the improvement of dual-use transport infrastructure are about 95% identical to those used by NATO. The three main advantages of such a system are:

- Simplifying and digitizing customs formalities to facilitate the movement of military assets across borders;

- Developing a digital system for quick and secure information exchange related to military mobility;

- Creating a unified IT network to enhance the efficiency of military logistics through the European Defense Agency.

Therefore, the future direction involves aligning domestic legislation with the norms of the Schengen Border Code. This will make the western border of our country more seamless.

Based on materials from the Information Agency Infopost

04.03.2024